From its very beginning, British hip-hop has existed in a permanently maligned state, seemingly always losing ground against the genres it rubs shoulders against. Whether being unfathomably overshadowed by its US counterpart, or rejected in favour of more frenetic grime, British hip-hop has always failed to become both culturally ingrained and critically successful. However, the scene has worked quietly in the niche forced upon it, forging over a number of years a distinctly British sound.

Initially making the jump across the pond in the 80’s, British rappers at first struggled to reimagine the music in their own unique way. This can be perceived most obviously in the adoption of American accents by many early British rappers, such as Derek B, who were unable to extricate the mode of performance from its roots. It sounds, in retrospect, frankly ridiculous, especially as such a large part of hip-hop is the expression of your own localised culture. This was a narrative broken by ‘London Posse’, who expressed the culture of our capital city in their own voices, whilst Jehst’s breakthrough album featured tracks such as ‘City of Industry’, giving a voice to post-Thatcherite Yorkshire, and Skinnyman’s Council Estate of Mind expressed the struggle of survival of those in the welfare state.

Whilst these rappers did much in their early work to express a localised identity, their beats were all informed massively by American heavyweights such as J-Dilla and DJ Yella. Enter Mike Skinner, whose aim to create a ‘British hip-hop 2.0’ entwined the storytelling aspects of the American scene with the distinctly British sound of garage. Whilst he argued that predecessors that rapped over garage tracks had lyrical content consisting purely of “going to the bar to have another tequila”, he wanted to rap about the real life of him and those around him, even if it was just “smoking weed and those little adventures you have with your mates”.

What Skinner did to create a British voice for hip-hop, was not only to extricate the music from its American roots, but also to reinvent an image of Britishness itself. The opening track of Original Pirate Material takes the centuries old British image of the soldier, but resituates it away from sites of war to the Birmingham bullring. Here, it becomes the ‘geezer’, a character which Skinner sees as the new British male. Central to identification with this character is behaviour rather than background. This theme continues throughout the album, ‘Has it Come to This’ demanding the listener should “pull out your sack and sit back, whether you’re white or black”. Skinner used hip-hop as a way to create and consolidate a view of what Britishness should be, a notion which many in the scene were also working towards, for example Roots Manuva’s ‘Witness the Fitness’ compares his family background of Jamaica and his adoptive home of Britain, through lyrics which move from “jerk chicken, jerk fish” to “ten pints of bitter”.

Skinner himself claims he had ‘no impact on UK rap’, but this modest claim is shattered by Contact Play, who similarly destroyed everything else in their path when they burst onto the scene with Champion Fraff in 2011. Contact Play’s hazy descriptions of powder-fuelled nights out are hugely indebted to the lager soaked vignettes which populate Skinner’s most famous tracks, but C.P’s self-defined ‘tour-de-force of all that’s raw’ can also be read as a suburban British interpretation of American gangster -rap. It works due to the group’s tongue-in-cheek boasts about drug consumption interspersed with attacks on middle class sensibilities. There is something mocking in all of Contact Play’s music, and where British imitation of American rap was once a weakness of the scene, C.P. transformed it into a sarcastic strength.

Hip-hop’s refusal to exist in a vacuum, continuously referring to other works, has helped make British hip-hop the most innovative and collaborative movement in our nation’s music scene. This can be subtle, such as Loyle Carner’s argument that grime gave him the confidence to rap, or it can be overt, with rappers such as Benny Mails’ often transitioning between grime and hip-hop within a track. There is a sense within British hip-hop that we are on the cusp of something new, whether it be born out of experimentation between genres, such as Mancunion group The Mouse Outfit dabbling in 160bpm tunes under the moniker Levelz, straightforward hybridisation pioneered by those such as Dave and AJ Tracey, or altogether new forms such as lo-hop quickly accelerating under artists such as Looms. One thing is for sure, with the amount of talent rising through the scene currently, British hip-hop won’t be in the fringes for much longer.

Reece Parker

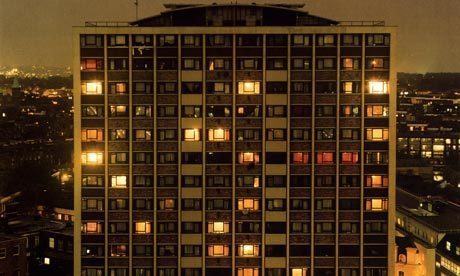

[Feature Image: The Streets Album Artwork for Original Pirate Material]