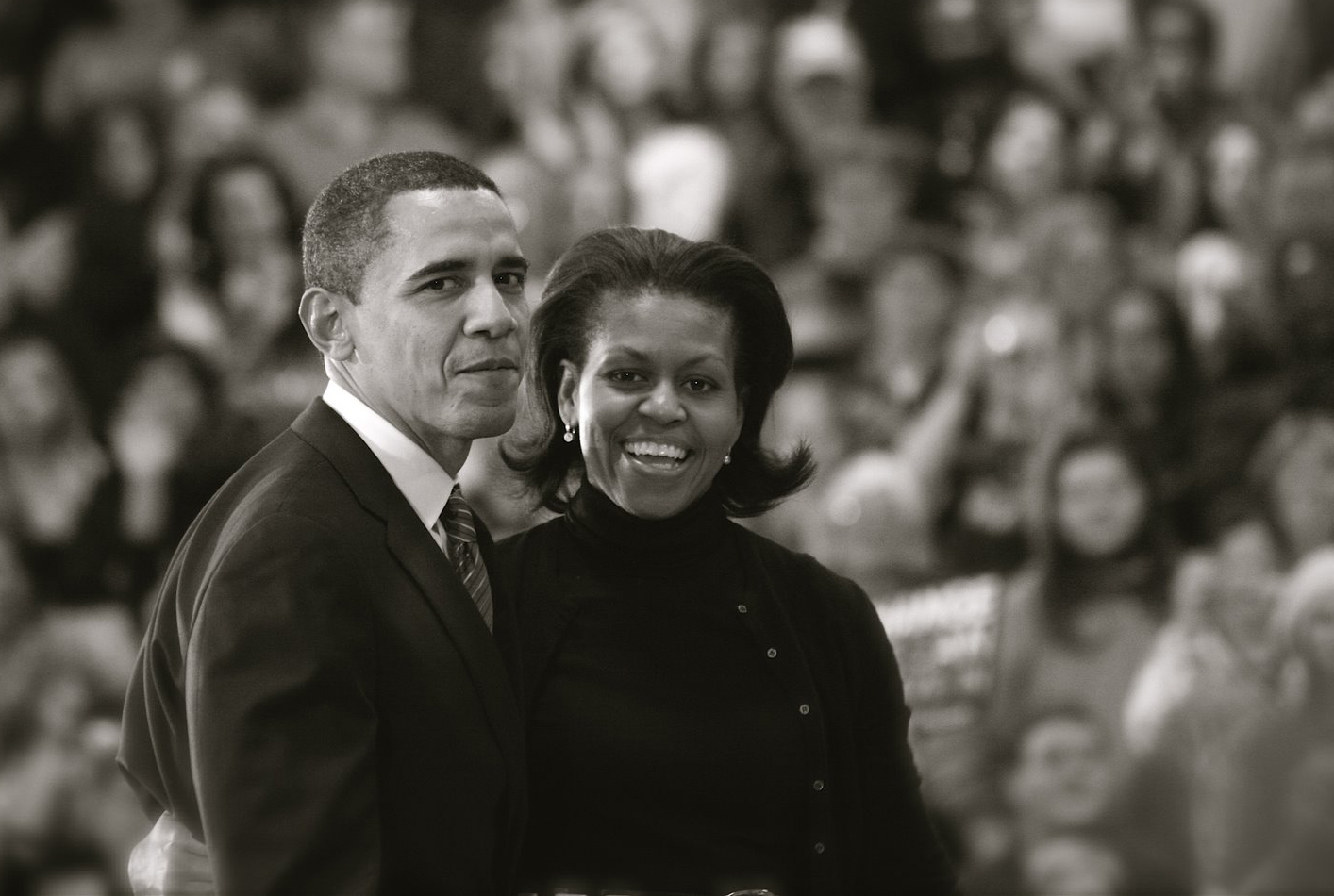

Obama’s choice for his and Michelle Obama’s official portraits are a break from tradition, as he opts for two artists whose styles explore an underrepresented part of American life.

The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery announced last Friday that Barack and Michelle Obama have chosen artists Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald to paint their official portraits; this will be the first time a pair of black artists have been commissioned by the gallery to paint the portraits of a Presidential couple after the completion of their term of office.

The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C first began commissioning portraits of the President and first lady after their tenure in the 1990s (beginning with George H.W Bush), with the exhibition being the only other collection of official presidential portraits outside of the one in the White House. The new portraits are set to be displayed within the gallery in 2018.

The artist chosen to paint Barack Obama’s portrait, Kehinde Wiley is an African-American artist well known for his naturalistic, vibrant portraits of people of colour, placing his sitters against backgrounds covered in intricate patterns taken from French, Islamic and West African art. Whilst not as well known as Wiley, Michelle Obama’s choice, Amy Sherald, paints equally vibrant portraits depicting black subjects from all walks of life, positioning them in front of block colour backgrounds.

But why do the Obamas’ choices matter for art? The election of Barack Obama in 2009 finally fulfilled the need for people of colour within political roles in American politics and the world; and the choice of two black artists for the presidential portraits also allows the Obamas to facilitate the celebration of the role of black artists within art history. Both Wiley and Sherald are exciting choices not only in their styles of painting, which go against the overtly formal, occasionally stiff renderings of past presidential portraits, but also in the way that they celebrate black culture in their respective works. For example, in his pieces Wiley reimagines past works of the great ‘masters’ (such as Titian or David), substituting the original (white, usually male) figures with people of colour in an effort to stress the significant presence of black people within history that is often ignored in the Western art tradition. As a gay man, Wiley also depicts homosexual black couples (such as in his 2008 work Dogon Couple), another subject which is highly underrepresented throughout art history. Sherald likewise celebrates black culture, but in a broader sense, depicting a diverse range of real people she encounters in everyday life. Like Wiley, Sherald only paints subjects of colour because, as she says, ‘There’s not enough images of us’.

The website of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery describes its exhibition of presidential portraits as one that ‘lies at the heart of the Portrait Gallery’s mission to tell the American story through the individuals who have shaped it’. However, as with many representations of the ‘American Story’ throughout time, all of the individuals represented in this particular exhibition have, up until now, been white. Thus, the choice of the Obamas helps to underscore the important role black people have played in shaping ‘the American story’, a choice that appears aptly timed, coming at the close of Black History Month. Even then, whilst Black History Month is something to be embraced and participated in, the work of Wiley and Sherald alone urges us to remember that the celebration of black history and black culture more generally should not be confined to one month out of the year, but should be integrated into our teaching of art and history everyday.

Hannah Stokes

(Image courtesy of Luke Vargas)