The iconography of the ‘Punk’ has been both popularised and reproduced at a staggering rate since its heyday in the late ‘70s. Beginning as a set of shared ideological values and musical taste, the infamous reputation of the ‘Punk’ lifestyle seems to go beyond simply a subculture in modern times. Whether it is nostalgically idolised or ignorantly generalised, it is an image which has often become misunderstood and commercialised. Even during the height of its popularity, those who considered themselves as ‘true’ punks often shied away from the label; it became another assumption to resist and rebel against. This desire to maintain a sense of integrity was, in my opinion, convoluted as a movement into the new millennium occurred. The digital revolution which accompanied this new era led to an immense ideological shift in which the original values of the ‘Punk’ can be seen to decline.

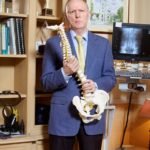

In 2016, the most viewed article from The Guardian Online was a piece entitled ‘Never mind the bus pass: punks look back at their wildest days’. This ‘then vs now’ study explored how modern life has ultimately affected some of the most dedicated rockers of the ‘70s and ‘80s. The ex-drummer of The Clash now appeared as a 59-year-old chiropractor while an ex-bass player now prided himself as an investment banker. It seems that both maturity and the passing of the millennium has propelled these individuals into lifestyles of conformity and acceptance. Ideas of rebellion are not coveted, celebrated or encouraged in the same way. It is then fitting to suggest that the values of the punk subculture depleted alongside a generation’s growing tolerance to the establishment; a notion which I believe to be catalysed by both an expectation to ‘grow up’ as well as the presence of important technological advances. It even becomes ironic to consider that this article gained prominence through online platforms; we now discuss the significance of punk subculture through mediums which were unheard of at its origin.

(Terry Chimes, former drummer in The Clash, then and now.Photograph: Alan Powdrill for the Guardian)

As a generation which seems to become alarmingly dependent on social media and possessing an online presence, there is a distinct opportunity provided to judge our ‘friends’ and ‘followers’. The use of online media platforms to construct an identity which may not adhere fully to our true selves exposes a lack of honesty and grittiness which seemed so intrinsically linked to the punk ideology. Social media also provides the chance to replicate the fashion choices and styles of those we see online. This idea of duplicity directly contrasts the values of a subculture which seemingly detested unoriginality and conformity. The sad irony of this can again be seen through the reproduction of band t-shirts. The logo provided from Ramones is plastered across various forms of clothing lines and is even sold in Primark. This level of commercialisation not only reinforces the prospect that punk has been transformed into a mainstream brand, but illustrates how modernity has ultimately tainted a non-conformist ideology.

In a world of Spotify and Apple Music, it can again be observed how the music of a particular subculture can now be messily entangled with other genres. Eclectic playlists are now able to be created at the touch of a few buttons with an access to almost any artist from X-Ray Spex to Stormzy. Consequently, the opportunity to mix and more carefully customise our listening in a way which was not available during Vinyl, again makes the once clear identity of the modern punk far more complex. Additionally, the prospect of routinely paying a fee to large corporate company again seems problematic. It is a bittersweet sensation listening to Sex Pistol’s ‘Anarchy In the UK’ on a site which also seems to contradict any movement away from the growing wealth of corporate industry. This complexity to understand one’s own identity in this new technological world has most recently been explored in Irvine Welsh’s T2:Trainspotting 2. Its revival from the original 1996 film follows the difficulties in adapting to a transformed society in which resisting conformity seems a much more challenging feat. This is again represented in the film’s respective soundtrack which combines the familiar punk artists such as Blondie and Iggy Pop with millennial artists like Young Fathers. The blurring of various musical genres alongside the depiction of characters engaging with a digitalised world is symbolic of this cultural shift.

It becomes clear that the true values of original punk subculture have become lost and convoluted in modern society. Technological advances and the ever increasing consumerist market ultimately has resulted in the death of the ‘Punk’. Modernism is now entrenched with a requirement to conform to technology and its respective celebration of materialism. We are now left in a world which to ‘Never Mind the Bollocks’ appears dated, out of touch and distant from reality.

Ellie Montgomery