In late 1970s Jamaica, popular music shifted away from its reggae roots towards a more modern, risqué and different display of culture. This new trend was called Dancehall and it was the first emergence of a global musical phenomenon.

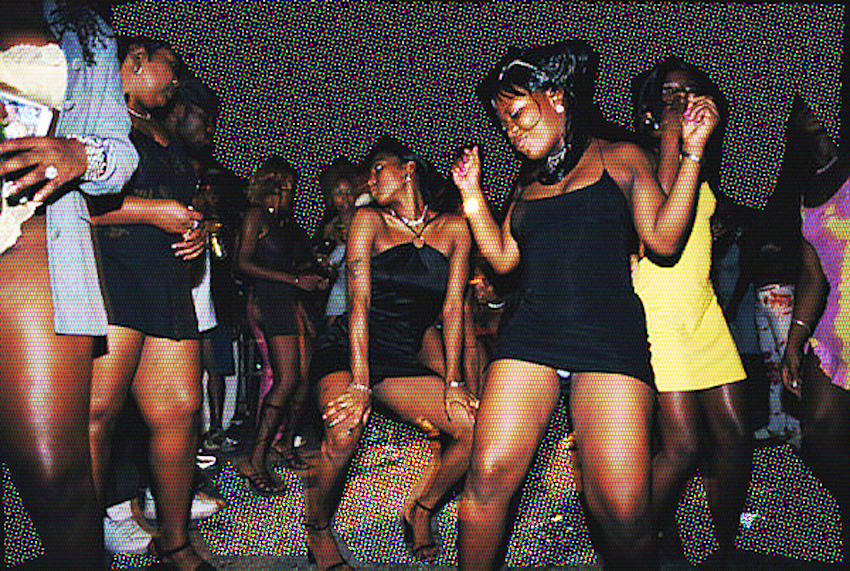

Physical dance halls had existed in the inner cities of Kingston since the 1950s/60s, blasting out popular mento, ska, rocksteady and reggae. This was a space where local sound systems played out Jamaican recordings to adoring crowds, with the kind of fame of presidential status. There were live performers, alcohol, food, and huge custom built ‘House of Joy’ speaker cabinets that attracted masses of Jamaicans to the party. In a racially divided society, where European culture was still held to higher regard, and African culture stigmatised, the dance hall acted as place of solidarity and solace for the marginalised in society. The dance hall was inner city, working class culture: a voice for the voiceless.

After the death of Bob Marley in 1981, the music began to change. Shifts from a government focusing on collective enhancement to the individualistic Jamaican Labour Party of the 1980s, meant that lyrics began to take on a new sense of self. Themes of sexuality, violence and dancing took prominence. Deejays like Yellowman and Shabba Ranks boasted of their looks and prowess, a form of individual advancement for the urban poor. Technological innovations around the art of DJing also meant that faster, digital rhythms could be produced and more deejays could jump onto the scene. With the creation of the Sleng Teng rhythm in 1985, it became possible to mix one digital rhythm with different voices; the ‘toasting’ (talk-over) dancehall style became easy to reproduce and easy to make. This was the climate in which dancehall, as a genre, developed and thrived.

But, the spread of dancehall couldn’t have been possible without the popular sound systems that helped to maintain it. Sound systems like Stone Love Movement, Aces, Inner City, and Metro Media travelled across the country, providing outlets for aspiring deejays and singers to perform at events and burst out onto the global dancehall scene. Impressively, the role of sound systems remains prominent today, but it is intertwined with the modern club scene and Jamaican media outlets such as Irie FM and Hot 102, as well as popular American outlets like MTV.

However, the popularity of dancehall has not been complete without its almighty controversy. Lyrics are accused of ‘slackness,’ or promoting misogyny, violence, sexual bragging, objectification and sometimes homophobia. Moral panic around ‘gangsta’ lyrics and ‘gun tunes’ meant that dancehall came to be seen as degenerative and a catalyst for violence in Jamaica. Today Notting Hill Carnival, where dancehall music plays a huge role, comes under repeated criticism from the media. Truthfully, there have been dancehall artists who have made homophobic comments, and this is a definite problem, and completely unacceptable. But aside from these artists, dancehall music as a genre is loud, colourful and vibrant. It is empowering for Caribbean people who have been marginalised, and faced the trials of history. Dancehall goes against fixed, inhibiting standards of decency; it is a political rebellion.

Today the vast majority of students, unknowingly or knowingly consume dancehall music. In popular music, Rihanna’s ‘Work’ was the first dancehall song to top charts since Sean Paul’s ‘Temperature’ in 2006. Drake’s ‘Controlla’ sampled Beenie Man’s ‘Tear off Mi Garment’ to both critical and public acclaim. Sean Paul and Beenie Man can be heard in every noughties throwback room in any club. We have events in Leeds like Clarks, Dancehall Science and groups like The Heatwave, filling their sets with artists who started in Kingston and made their way to the top. Enjoy the music, have a dance, and lend an ear to the history that made it all possible.

Amelia Whyman

(Image: superselected.com)

One thought on “Dancehall: A History”