Most music fans are no doubt already familiar with David Bowie’s pioneering stage personas and continual reinvention. More dedicated followers will be well versed in how these traits encouraged fearless self-expression and pride throughout the LGBTQ* community. But relatively few Bowie lovers will be aware of how the icon incorporated Polari, a language used by gay men in the sixties, into his swansong masterpiece, Blackstar.

With homosexuality being a criminal offence in the UK until 1967, gay men and women found the need for a language they could use to communicate with one another without revealing their true identities to a prejudiced public. This is where Polari came in. This niche language, known linguistically as a dialect, consisted of words and phrases that sounded like complete nonsense to those outside of the social circles that used them. In reality, it was a creative and vibrant lingo which enabled LGBTQ* people to talk about their love interests and sex lives safe in the knowledge that they wouldn’t be mocked or, worse, arrested. The great irony of Polari is that it eventually became so popular that it fell out of use. With so many speaking it, code words became common tongue, and Polari could no longer function as the secret language it was intended to be.

It’s on the Blackstar track ‘Girl Loves Me’ that Bowie acts Polari-revivalist, and it’s fitting that arguably the most avant-garde song on the album features the most esoteric lyricism. Though the song is largely written in Nadsat, the fictional language used in A Clockwork Orange, the Polari terms can be found in the lines “Cheena so sound, so titi up this malchick, say / Party up moodge, nanti vellocet round on Tuesday”. “Titi”, a shortening of “titivate”, means “pretty” or “fix up” in Polari, and “nanti” translates to “not” or “no”. So, while the exact meanings of these words are up for debate, the lines translate approximately to ‘Girl so sound, so pretty up this boy, say / Party up man, no drugs round on Tuesday’. For me, this is evocative of the same glitzy, drug-fuelled hedonism heard in the Hunky Dory romp ‘Queen Bitch’, in which Bowie sings of Flo ‘hoping to score’ whilst ‘looking swishy in her satin and tat’. Both songs also conjure up vivid imagery of gender fluidity: ‘Girl Loves Me’ with “pretty up this boy”, and ‘Queen Bitch’ with “Oh God I could do better than that” in reference to looking feminine.

Elsewhere in English rock, indie icon Morrissey, an artist equally as famous for his sexual ambiguity as Bowie, has also incorporated Polari into his lyricism. The opening track to his 1990 album Bona Drag, ‘Piccadilly Palare’, has him crooning the words “so bona to vada, oh you, your lovely eek and your lovely riah”, which roughly translates to “so nice to see you, with your lovely face and lovely hair”. It’s a typically flamboyant number with fairly explicit references to male prostitution in London and, with the title presumably an alternative spelling of ‘Polari’, Morrissey was keen to emphasise this facet of the record. Even the album itself is titled in Polari, equating to ‘good clothes’ in English.

Polari helps create the song’s darkly sexual and sinister tone. ‘Girl Loves Me’ is a sparse and syncopated five minutes with an ominous, stalking bassline and haunting vocals. By using this dialect with sexual connotations, Bowie unstabalises his listener; we are presented with a language that is unfamiliar and unsettling. Furthermore, the song is an example of trademark Bowie lyricism. Throughout his untouchable career, he thrived on creating meaning through deliberate ambiguity, leaving it to the listener to extract what they could from the words on the page. ‘Girl Loves Me’ may have little in terms of a clear narrative, but the use of Polari is far more significant in how it creates the mood of the track than in how it might convey an exact message. In writing “nonsense”, Bowie allows his listener to make sense of the song in whatever way they wish.

‘Girl Loves Me’ and the rest of Blackstar will no doubt elude attempts to define them for years to come, perhaps indefinitely, but one thing is clear: after a lifetime of advancing the cause for people wrongly considered abnormal, David Bowie continues to introduce and champion LGBTQ* culture, even in death. It’s a final, ingenious show of creative flair which typifies his entire body of work and is something we can all remember him by.

Tom Paul

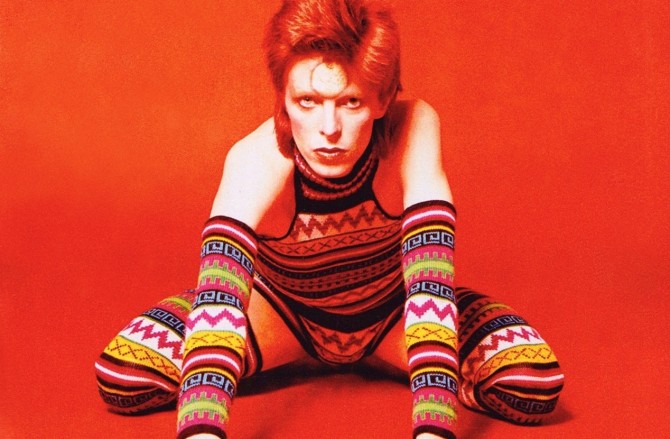

(Image: Queerty)