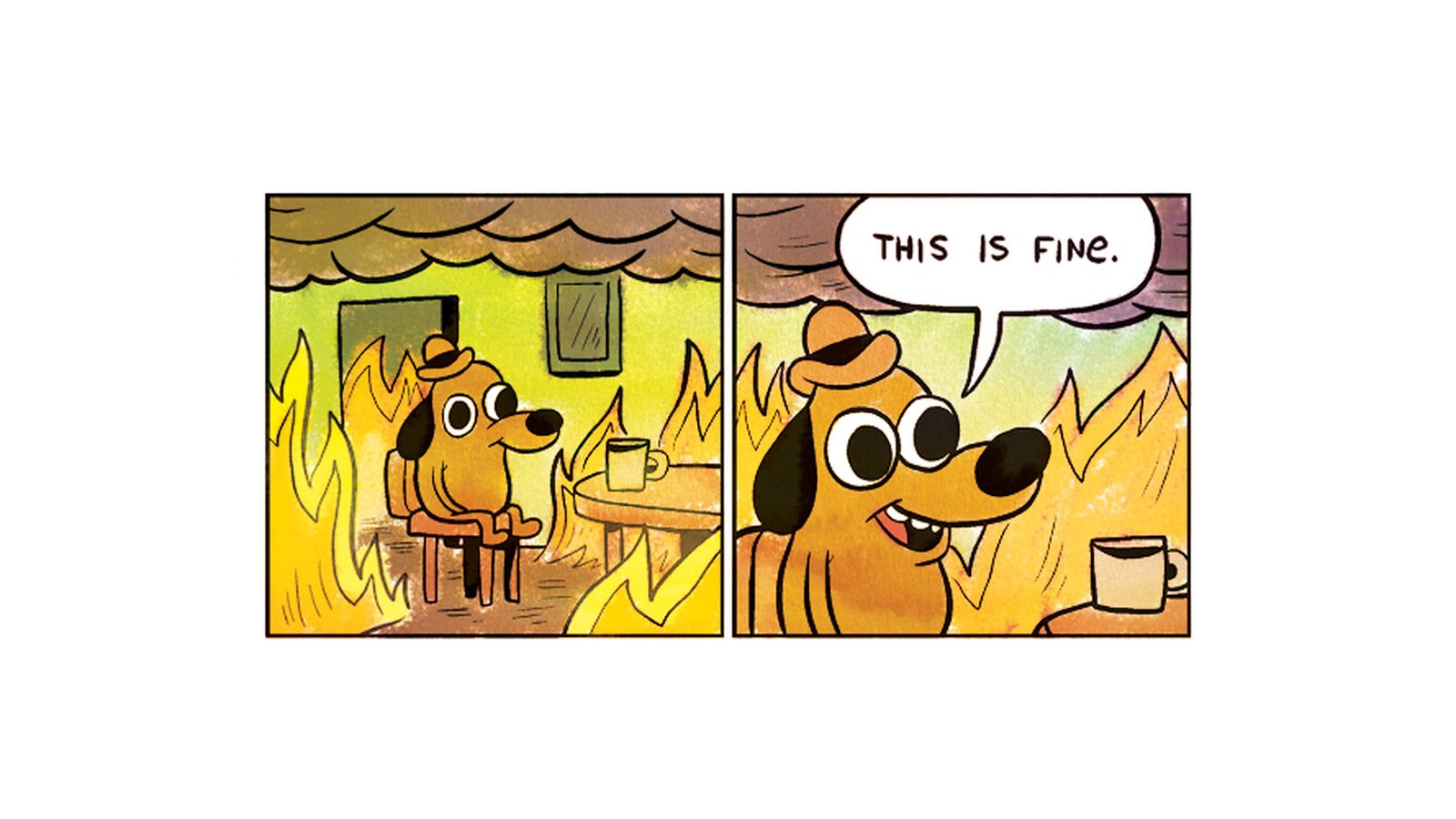

Edmund Goldrick outlines the danger with the ‘tough it out’ attitude towards illness in the work place and university. Who’s at risk? And what should we be trying to change?

Catch any bus, go to any university lecture, office, supermarket, and you will likely find clearly sick people toughing it out and carrying through with their day. It is reflective of confusing workplace protections around sick leave, the social pressure to work and study, and a lack of awareness of the risks.

Currently, workers are required to be sick for four consecutive days before applying for paid sick leave. This is unhelpful, as it asks workers to project how long they expect to be sick for. Even if they do get paid sick leave, what you will receive is a pittance of what you’d be paid if you were at work. Average weekly pay in Britain is around £500 a week, while the average paid sick leave is only £112 a week (the minimum weekly sick pay being £88.45). Unsurprisingly, research cited by The Independent indicated that Brits took, on average, 1.85 days of paid sick leave in 2015. Though up from an alarming 0.93 in 2014, it is nowhere near the pre-GFC average of five days. That the average falls well below the required four consecutive days suggests most people are never able to get paid sick leave.

This echoed the concerns of one part-time Leeds University worker, who, despite being very ill, lamented, “If I stay home, that’s £50 I’ve lost, so it’s just not worth it”. The situation is more convoluted for people on zero hour contracts. Citizens Advice says people on zero hour contracts ‘may’ be able to get sick leave, but gives no indication of what circumstances allow you to get it. They instruct workers to ask for a reason from their employers if they are denied it, and to contact them if they are unhappy with the response (again, no indication of what constitutes a valid reason for being denied paid sick leave). ACAS (Advisory, Conciliatory and Arbitration Service) however, alleges that most zero hour contracts give people ‘worker’ rather than ‘employee’ status and so do not give the person a right to paid leave.

A recent report by the Public Library of Science and the New York Department of Health stressed the importance of paid sick leave in encouraging contagious people to stay home. However, the influence of such studies is countered by pharmaceutical studies, and news reports on sick leave that focus on ‘how much money was lost’ by people taking sick leave. They make no effort to assess the economic gain of sick people not working; namely, it reduces the risk of contagion to colleagues. This is despite that avoiding further contagion is, understandably, the medical priority.

Aside from economics, there’s also an issue of vulnerability. While many may be able to work through an illness, others may not be so lucky. This includes people recovering from surgery, with auto-immune diseases, struggling financially or with their studies. In the latter case, research at the University of Minnesota found that an extraordinary proportion of students who had symptoms well beyond a cold were still attending all their classes. Around 40% of students displaying Influenza like illness (ILI) maintained constant attendance.

This ‘tough it out’ attitude persists at Leeds, with one student boasting he managed to continue to attend all his classes despite having ‘rhino flu’. While some classes have good mechanisms for recording either the lectures themselves or noting the vital content, for others attendance is much more crucial to success, and absence through illness is going to present enormous difficulties.

There is even little encouragement for basic measures to prevent spreading illnesses if you are sick, such as coughing into one’s arm rather than a hand, or wearing a mask as in done in much of Asia. The latter would be a particularly sensible measure if sick, and one’s classes demand attendance.

Unfortunately there is little will to change any of these areas. Be it more sensible paid leave arrangements, public health campaigns, or more support to allow students to be able to miss classes through sickness, but still keep up with their course. It seems the persistent ‘grin and bear it’ attitude still prevails, at the risk of not only the sufferer but other students and colleagues.

Edmund Goldrick