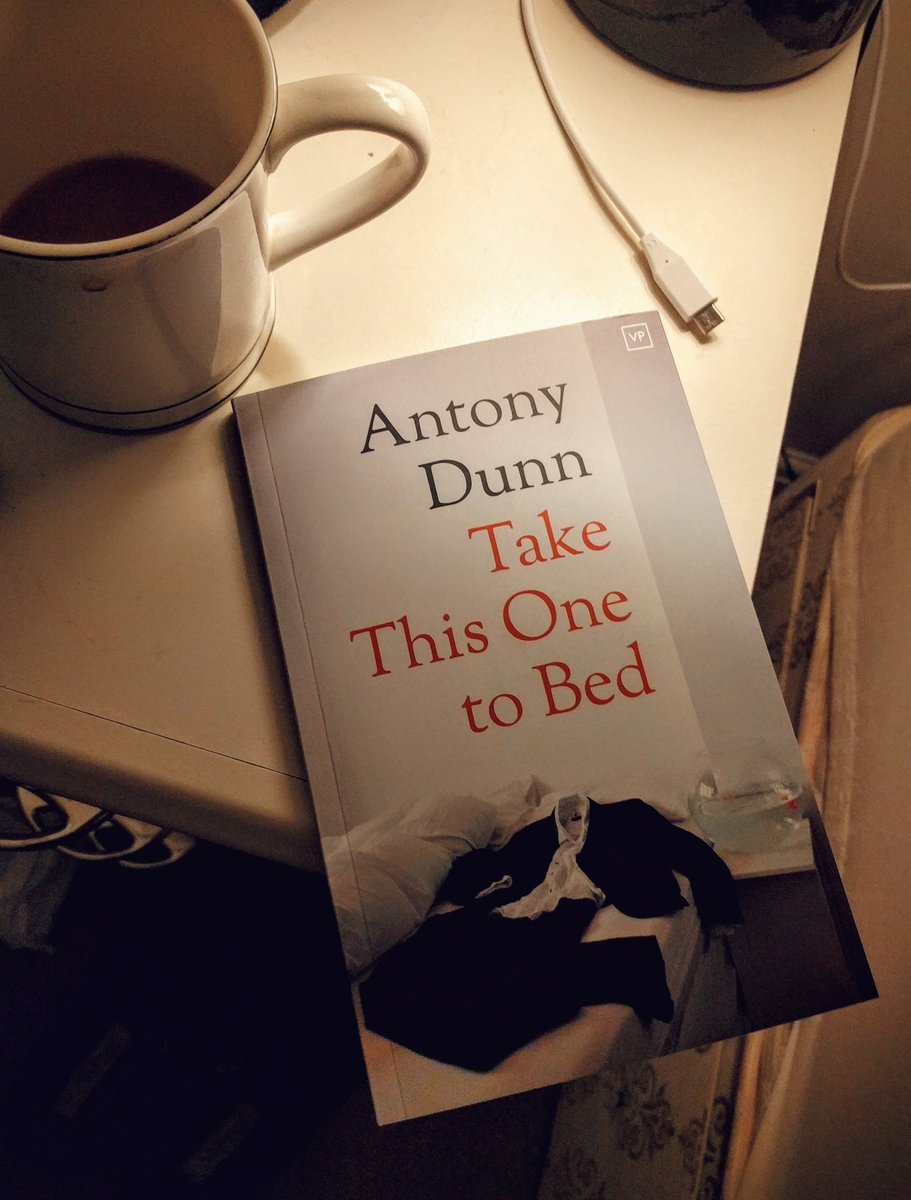

Antony Dunn’s anthology Take This One to Bed at first presents itself as a sultry invitation, and you open the pages expecting to see hymns written to the female body – or at least some thinly veiled allusions to sex. Instead Dunn gives you the intimacy evoked by the suggestive title instead, in some painfully recognisable, but yet obviously personal verses.

Many of the poems seem to chronicle a relationship in its various stages. Dunn’s poems make you feel like you’re prying through a bedroom window into his marriage, and you don’t always find what you expect to. In the title poem ‘Take This One to Bed’ Dunn’s sparse writing painfully conjures a couple at the stale end of an argument. Elsewhere, the narrator’s son and his pet goldfish make a surprising, but oddly poignant recurring appearance, as he and his wife struggle with the day-to-day workings of a marriage – how to tell their son the news, and then how to tell him of their separation. In ‘Leaving iv. Departures’ the poet writes ‘I cannot pinch this distance closed with tender thumbs’ and the bed in the title suddenly feels empty and very lonely.

Elsewhere, the poems are painfully self-conscious. Dunn paints pictures of his old school friends now out-of-touch in ‘Eighteen’ – everyone can recognise the wistful finality of the last line ‘we will not be this way again.’ Dunn is a local poet and two matching poems ‘Leeds to London’ and ‘London to Leeds’ capture exactly the odd transient atmosphere of the journey many of us know so well. But perhaps my favourite poem of the collection is ‘Animal Rescue’. The narrator lists the small defenceless creatures he has helped over the years, the insects he has carried out of his home and set free. I won’t spoil it for you, but I think this poem achieves what all good poetry does – perfectly nailing a feeling, in this case vulnerability, in a way that has not ever been done before.

Dunn is a poet firmly situated in the present day, with references to the radio and even Facebook in many of his poems, each only adding a layer of reality to the stories he’s telling, rather than perhaps spoiling the art as you might have first assumed. ‘Portrait of poet with a dimmer-switch’ takes the eternal image of the artist at his desk and updates it, but the sorting through of feelings – that’s the same as ever.

At points this constant self-examination can feel slightly indulgent but in other places Dunn’s tendency towards introspection results in his most successful verses, like in ‘Spider Hours’ – a new take on the old wives’ tale of swallowing spiders in your sleep. Dunn’s entrusting us with his poems, asking us to take them to bed and with the same confidentiality his poems create.

Heather Nash

(Image: @AntonyDunnPoet – Twitter)