Acid House rose to prominence in the 1960s to the 1980s from the clubs of Chicago, characterised by the ‘squelchy’ sounds of the emerging bass synthesiser, the ‘Roland TB-303 Bass Line’. By the late 1980s the sound had travelled to Ibiza, where DJs Alredo Fiorillio and Jose Padilla were spreading the genre in the sun and warmth of clubs like Amnesia and Pacha. Here it was found by a group of small time DJs and business opportunists, Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling, Nicky Holloway and Johnny Walker, in search of the best parties and new scene. Excited by the new style of music and a newfound ecstasy culture, they brought the sound back to club nights in South London hotspots. The plan was to reinvent the carefree, trendy, ecstatic Ibiza holiday and turn it into something that could inspire Thatcher’s mundane, individualist Britain. The revolution into a new culture had begun.

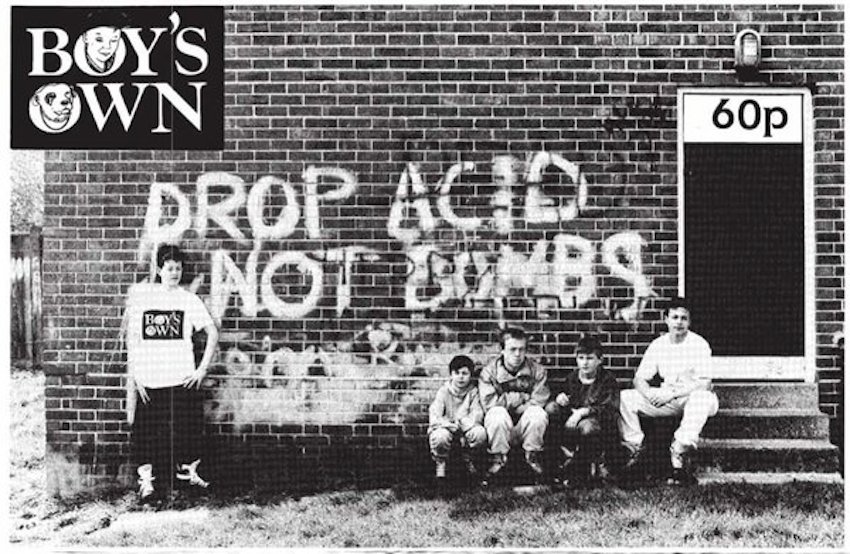

What followed was the explosion of a music scene into a rave culture. In Manchester, Ibiza nights at The Hacienda became a hub for acid house ravers who travelled across the county for the ‘Madchester’ experience. Clubbing attire changed from suits to dungarees, as ravers strayed from identifying with the clothing of a white-collar worker and took to colourful baggy sweatshirts, Doc Martens and Levi 501’s. In London, Shoom was the first club to don the yellow smiley face logo that became a sign of membership to this acid house community. The Trip, a house night at the Astoria, was also filled with acid house enthusiasts in outlandish clothing, with club-goers spilling onto the streets at the end of the night, still reeling from the deep baselines and electronic beats.

The popularity of Acid House was not complete without the presence of recreational drugs, and open drug taking became standard at these events. The empty industrial spaces of factories and fields, themselves a product of Thatcher’s Britain, became the perfect setting to escape with the help of psychedelics. The dark side of the culture bears mentioning here. In 1989 16-year-old Claire Leighton collapsed and died as a result of taking ecstasy at the Hacienda. This was the first ecstasy death in the UK. In 1995 Leah Betts died after taking an ecstasy pill and then drinking seven litres of water in a 90-minute period. The Hacienda couldn’t shake the presence of violence, drug dealers and gangs. The club closed in 1997. What was meant to be the ‘Second Summer of Love’, with dancing, good music and wacky clothes materialised into something more sinister.

Just like how mods and rockers became folk devils of the 1960s youth generation, shown as violent gangs who couldn’t help but fight with each other, acid house fell victim to demonisation and moral panic. When people starting dying of ecstasy, Acid House couldn’t be seen as a fun new craze anymore; it lost itself to negative exposure. Ravers were labelled ‘Drug Crazed New Hippies,’ Police cracked down on clubs and raves and 1971’s Misuse of Drugs Act attempted to put a stop to usage. The 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act contained a whole section on control of raves. This 1994 act is where hysteria is most obvious. A rave was defined, by law, as a gathering in open land or air with music that is ‘predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.’ This was an almost comical attack on an alternative culture. How could the government’s fears over a scene mean that its musical genre could be pin-pointed by law and directly attacked?

As we all now know, young people would fight back. The Reclaim The Streets collective picked up speed. Raves became a point of political resistance, where young people were battling over their rights to use public space. Such spaces were occupied and ‘free parties’ were put on, taking inspiration from ‘Stop the City’ protests of the 1980s. Musicians also joined the resistance. The Prodigy’s ‘Their Law’ was a direct response to the bill. Lyrics include ‘what we’re dealing with here is a total lack of respect for the law’ ‘Fuck ‘em and their law.’ The booklet for their 1994 album said, “How can the government stop young people having a good time? Fight this bollocks.” The Streets’ classic ‘Weak Become Heroes’ from Original Pirate Material contains the lyric ‘and to the government I stick my middle finger up with regards to the Criminal Justice Bill.’

In short, government hysteria over youth culture made this culture more profound, and much cooler. Just as the 1960s repeated itself in the late 1980s with Acid House, what will the moral panic over the new generation of young people be? With the closure of Fabric in 2016 after its licence was revoked following high profile drug related deaths, could there be a growing public panic over recent clubbing culture? History seemed to repeat itself as the club’s closure sparked a ‘Save Fabric’ social media campaign, and the club reopened in January 2017 to a sell out event. Perhaps the irony of panic over club and youth culture is that, in an attempt to crack down, culture is strengthened and becomes a movement rather than a craze.

It would be wrong to disregard drug deaths and assume there is no problem: there is. But those fighting for the reopening of Fabric are the same people fighting for the right to hold raves in the 1980s. Club culture and music is cyclical. It will come around again and needs to, for life is quite boring without the next best, forbidden thing around the corner.

Amelia Whyman