Is it possible for us to exploit something that is potentially harmful to us, to alleviate something that might cause even greater harm? That is the big question for researchers in Leeds and around the world, currently working on oncolytic viruses. An oncolytic virus has certain characteristics that enable it to kill cancer cells, while sparing the surrounding healthy tissue. This may all sound a bit sci-fi-esque, however one such virus has been recently approved by the drug administrations in both the US and Europe, for treatment of severe skin cancer. This virus, which has the potential to eradicate skin cancer lesions, is the very same which causes your ever-annoying cold sores (herpes virus).

So, how is it possible for a virus – consisting of nothing but a few genes, a handful of proteins and is unable to sustain its own life – to potentially rescue us from life-threatening diseases? Viruses require a suitable host cell to multiply and spread, and as it turns out, cells that have transformed into cancer cells are particularly suitable hosts. During the transformation from a normal healthy cell into a cancer cell, the built-in defence against viral infection is lost – basically leaving the door open for any virus to invade. In addition, cancer cells often present proteins on their surface which are necessary for the virus to be able to enter the cells, much like leaving a pile of sweets in front of that open door. Once the virus gets inside the cancer cell, it can hijack the cell machinery to multiply, eventually to an extent that the cell bursts and dies. This leads to a release of new viral particles, which can infect surrounding tumour cells and result in a self-amplifying treatment.

The cells of the immune system are usually potent killers of anything they recognise as foreign to the body, such as bacteria, viruses, and even cancer cells. However, cancer cells often generate an immunosuppressive environment to surround the tumour, protecting it from attack by the immune system and allowing further growth and spread. There have been many studies showing that, in addition to their direct killing effect, oncolytic viruses can also activate the immune system, acting as a potent trigger for immune cells. The boost from a viral infection can wake the cells up from their suppressed state and engage them in identification and killing of cancer cells. It can also potentially generate immunological memory to provide long-term protection against recurring tumours. This further contributes to the efficacy and specificity of oncolytic viruses as a treatment for cancer, with one of the main advantages being enhanced selectivity for cancer cells over normal cells, compared to commonly used chemotherapies.

The University of Leeds is one of the big contributors to advancing oncolytic virus research in the UK, with several research groups studying a range of different viruses and their potential as treatments for many different cancers. Following on from numerous preclinical studies in the laboratory, formerly led by Professor Alan Melcher, the university has hosted several clinical trials as part of the development of a common cold-causing virus (reovirus) as a therapeutic agent. Only last week, a study completed by scientists based at St. James’s University Hospital was published in the BMJ journal Gut, demonstrating for the first time that reovirus also has potential as a treatment for primary liver cancer. There have also been great advances in other areas of cancer research; Professor Susan Short recently secured funding to start the first-ever clinical trial in the UK using an oncolytic virus to treat brain cancer, a disease where treatments with enhanced efficacy are urgently required.

These are only a few examples of how the daily work performed in the Leeds laboratories by students, post-docs and technicians significantly contributes to the fight against cancer. If you are interested in oncolytic virus research for an undergraduate or postgraduate project, more information and contact details for involved researchers can be found on the research pages of the Leeds Institute of Cancer & Pathology website.

Louise Müller

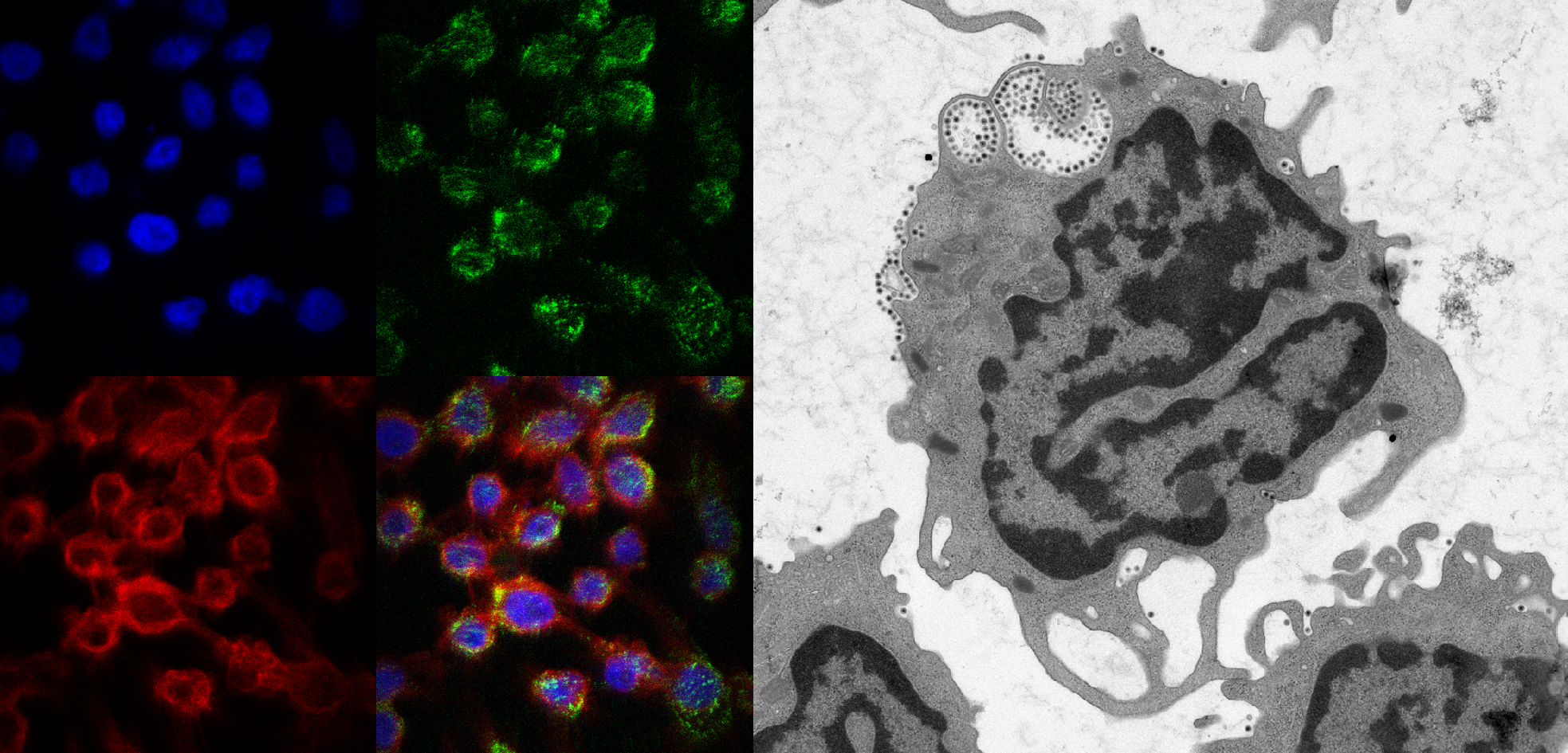

(Image courtesy of Rob Berkeley, PhD student, University of Leeds & Aat Mulder, Leiden University Medical Centre)