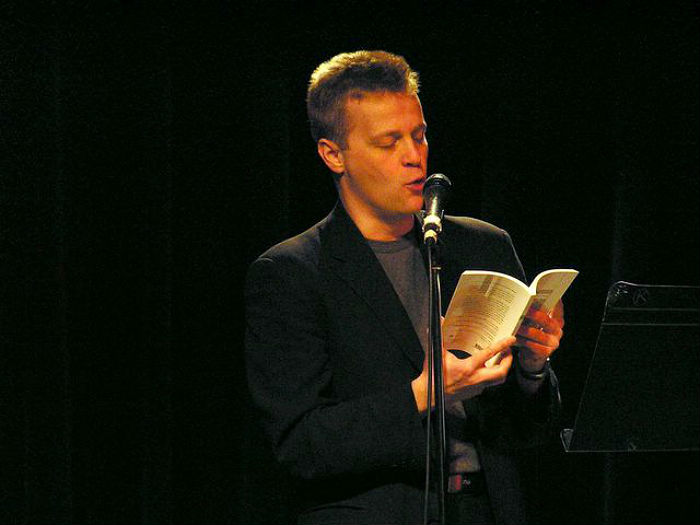

Experimental poet Christian Bök is renowned for his outlandish and complex poetic process. His theory appears to be that by putting enough constraints upon himself when writing, he will be able to access new levels of meaning, push the boundaries of language itself, and reconcile the seldom-reconcilable fields of art and science. He has won awards and been dubbed both a genius and a fraud. Last week he performed at Leeds Beckett University.

He opened with a few extracts from his best-selling book Eunoia, in which he writes each chapter adhering to the constraint that he can only use one vowel throughout – leading to sentences such as ‘Awkward grammar appals a craftsman’. These extracts were as fascinating as they were beautiful, as Bök managed to imbue the vowels with a deep poetic meaning, whilst drawing attention to the creative possibilities that lie dormant in every letter. I was, dear reader, lulled into a false sense of security.

‘These extracts were as fascinating as they were beautiful, as Bök managed to imbue the vowels with a deep poetic meaning’

At this point, Bök began to read exerts from his latest book, The Xenotext. The process behind this is mind-bogglingly complicated. As far as I (with my B in GCSE chemistry) could make out, the Canadian poet had written some poems, and then exchanged each poem for a series of chemicals, with each word being represented by its own particular chemical. He would then combine the resulting poem with e-coli in a petri dish (your guess is as good as mine) to see what ‘poem’ was produced as a result. Bök claims that his ultimate goal with this is to create an artwork that will ‘outlast the human race and live on for billions of years’. I can only say that I sincerely hope it does not. If, as Bök surely hopes they will, aliens stumble upon his poems billions of years from now, they will only be able to conclude that the human race were a pretentious and dour bunch, obsessed with finding endless synonyms for the word ‘destruction’.

‘If aliens stumble upon his poems billions of years from now, they will only be able to conclude that the human race were a pretentious and dour bunch, obsessed with finding endless synonyms for the word ‘destruction’.’

Following the reading, the experimental poet answered several questions from the audience, which I found to be rather illuminating. Yet again I was conflicted in my response. On the one hand, an answer regarding his process behind a love poem written in response to Romantic poet John Keats left me in awe. It was quite clear that Bök is a poet possessing considerable talent. On the other hand, his self-indulgent espousal of words such as ‘perfect’ and ‘genius’, left me feeling queasy. It is quite clear that Bök is a poet possessing an inordinately large head. It is this very narcissism that appears to underpin his latest work. Whilst one could potentially say this of all poets (after all poetry is a heartless art), I could not help but feel that these poems were for nobody, but Christian Bök himself.

‘I could not help but feel that these poems were for nobody, but Christian Bök himself.’

I concede that I may be on the wrong side of history here; in the future he may be ultimately judged a genius, and I a fool. But for now, I can only attest to my own opinion: that Christian Bök’s ambition considerably outweighs his grasp.

James Candler

(Image courtesy of DiverDapper magazine)