The Ancient Egyptians, Vikings and modern Christianity – all major civilisations and belief systems throughout history have had some predications concerning life after death. In contrast to these beliefs others have attempted to stop or, at the very least, stave off death. Just look at the wonders of modern medicine. But what happens if we try to go in another direction? What if, rather than extending life, we try to bring it back once it’s gone? This is the garish question some of history’s mad scientists have tried to answer.

Some of the earliest attempts at reanimation were carried out in the 1790’s by the Royal Humane Society of London. They thought that under certain circumstances corpses were not actually dead; rather they were in a state of suspended animation. The Royal Humane Society sought to establish methods for reanimating these corpses, as well as share their knowledge of reanimation across the world. Almost all of the methods they tried were inevitably crude, including the application of electricity, massaging the corpse and the use of liquor forced down the throat of the deceased. As bizarre as these methods seem now, they actually spread across sections of the western world, in particular across the pond. During 1973 The Medical Society of South Carolina purchased specialised reanimation supplies from the Royal Humane Society, attempting to raise public awareness of the possibility of resurrecting the dead. The result of this was a law, passed in August 1793, which required all owners of places that sold alcohol to take in persons deemed “dead” and use the Society’s techniques to bring them back to life. This was because “spirits were a key ingredient to the process of reanimation”.

While it eventually became apparent that these procedures did not raise the dead, these were by no means the strangest attempts made throughout history. By the beginning of the 19th century a great deal of emphasis was placed on electricity as a means to reawaken the dead. One of the reasons for this was that the concept of electricity was not fully understood, with the effects of an electrical current viewed as almost magical. During the early 1800s physicist Giovanni Aldini carried out a series of twisted experiments, involving the use of electricity in an attempt to reanimate dead animals. Aldini started out demonstrating how the application of a current could send dead frogs and other animals into twitching spasms. His experiments quickly devolved and – in one particularly gruesome display – he applied a large current to the decapitated head of an ox, which began to convulse and spasm as if alive. Eventually Aldini graduated from animals to begin performing his experiments on humans. He was able to procure a steady flow of freshly executed criminals, applying a current to their freshly decapitated heads. This caused the disembodied heads to grimace, convulse and twitch. After years of dreadful experiments Aldini finally got the recognition he craved, receiving an invitation to perform one of his experiments at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. In 1803 he performed his experiment on a hanged man, named George Forster, where witnesses reported the body was on the verge of coming back to life. This recognition – by a well-known medical body – bolstered the belief that electricity could be used to cheat death.

As we started to understand more about electricity, alternative reanimation experiments began to pop up around the 1930s – mostly using dogs as subjects. One rather infamous figure in the field of canine resurrection was the American biologist Dr Robert E. Cornish, of the University of California. He theorized that a dead subject’s life could be restored if the body was swung up and down rapidly, simulating blood circulation, while at the same time being injected with a concoction of adrenaline, liver extract, blood, and anticoagulants. Cornish would asphyxiate the animals then, after death, start the revival process.

Initially he suffered various failures, however his 4th and 5th experiments were allegedly brought back after being dead for 30 minutes. While the dogs – named Lazarus IV and V – had sustained severe brain damage, Cornish reported that after several days they were able to hobble around, sit up and even eat of their own accord. He claimed he had perfected his technique and in 1947 had the opportunity he desired; to perform his experiment on a human. At the time Cornish was contacted by a convicted child murderer, who had heard about his experiments and was willing to offer his cadaver for experimentation following his execution. Cornish made his preparations, even manufacturing the machine he had planned to use, however the prison warden’s opposition halted his plans. Public opinion was also against Cornish, particularly the moral dilemma of what to do with the criminal if the whole bizarre experiment actually worked. If the criminal was put to death and then revived, had he technically served his sentence and was then free to go?

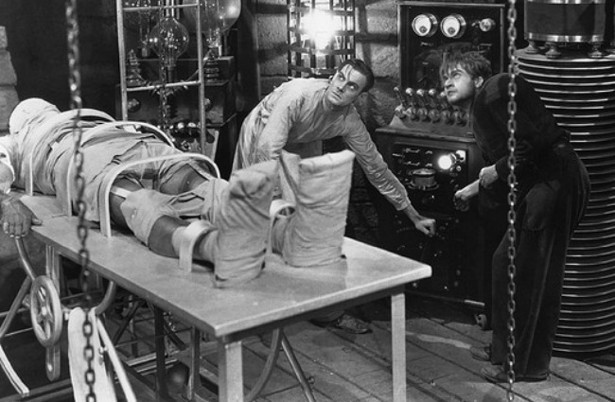

In the end, thankfully, Cornish never got his chance to bring a person back from the dead. Since those dark days we have come to understand cell biology and the process of cell death. Combined with a shift in the morality of human and animal testing, these Frankenstein-esque experiments gradually became nothing more than horror stories done in the name of science. It would appear that reanimation is nothing more than the pipe dream of mad scientists, barring an actual miracle or magic. That would, however, be the basis for a whole different type of story.

Steven Gibney

(Image courtesy of Insomnia Cured Here)