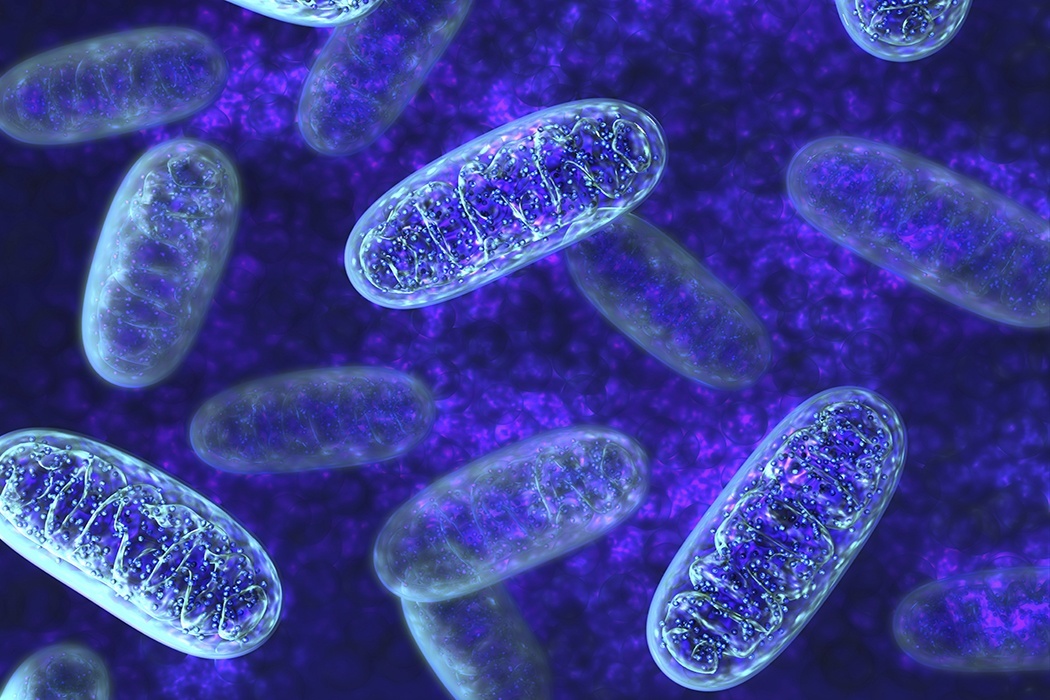

Ethics is an ever-present concern in science. No more so than when science clashes with human life itself in, for example euthanasia. That’s one of the concerns surrounding a treatment which has been developed to treat faulty mitochondrial DNA.In essence, mitochondria are the power stations of the cell. They supply your body with the energy to do everything. They also have their own DNA, inherited from your mother. If your mother is a carrier of a mitochondrial syndrome, you will have the disease as you get all your mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from your mum. Complications can have serious life-limiting results, up to and including death.

Now we know there’s a problem and who it will affect, so we should treat it right? A treatment does exist, involving removing the nucleus of an embryo from its cell and inserting it into a different cell from a donor which has had its own nucleus taken out. Translate that through a mainstream press prism and you get the headline “3 Parent Baby”.

Some people are uncomfortable with this, citing concerns this is beginning of an attempt to engineer a child and the Brave New World-esque idea of designer babies. Human beings created with certain traits erased or inserted according to a prescribed function or role or just plain whim and desire.

Others use a comparison with Frankenstein, which is easier because it has been made into more successful films, to make the same point: “Damn science! You scary!” However, the wheels of progress keep turning in the various corners of the world of science. Last month news broke that a group from New York have successfully used the treatment to produce a child who seems to be free of their faulty mtDNA. Dr John Zhang of New Hope Fertility Centre was photographed holding the newborn, born to a couple who had previously lost two children to the mitochondrial condition, Leigh’s Disease.

An abstract for the case has appeared in Fertility and Sterility, reporting the boy appears to be healthy at 3 months with only between 1 and 2% of the DNA remaining. Many have raised concerns; viability is one, with some pointing out that there’s no published data yet and that, so far, it’s just a claim. Others have pointed out that for the US to ban a treatment which is only going to be carried out more cheaply and less securely in places like Mexico is not the best way to guarantee either efficiency of safety. The procedure was approved for use in the US but the US congress blocked the legalisation of the process. Therefore, they did it in Mexico instead, like all things that disapproving US politicians try to block.

What about the ethical concerns? Generally speaking, it seems a lot of the problems wider society has with this treatment don’t reflect the worries science itself has. It suggests, to my mind, people who are worried need to understand the treatment and the loss and pain it can easily prevent. It’s hard to ignore the fact though this treatment couldn’t be performed in the US, which is tempting to ascribe to Congress labouring under almost a superstitious mediaeval view of fearing science as a meddling in nature. The problem all of these views point to is the unwillingness to concede that we are not special as we like to think; that we’re merely a biological process that can be modified, like Mendel breeding his pea plants. Unfortunately, we really sort of are in that we can understand and modify the basic processes that give rise to human life, in the same way that we can easily treat some illnesses by giving medication to manipulate our body’s chemistry.

The ethics science is concerned by here are more pedestrian but no less important.Verifying the process is a serious concern for science and ensuring best practice is followed. The fraudulent claims of Hwang Woo-suk, a South Korean vet biotechnology professor, who said he had successfully cloned a human being spring to mind.

Ethics in science is often less about worrying if we’ll perfect a human but more doing imperfect work. But if the scientific process is being done well, I don’t think we should be concerned by “three parent” children. Having the technology and means to save and improve lives and choosing not to do so however; now that’s unethical.

Leo Kindred

(Image courtesy of iStock/Getty Images)