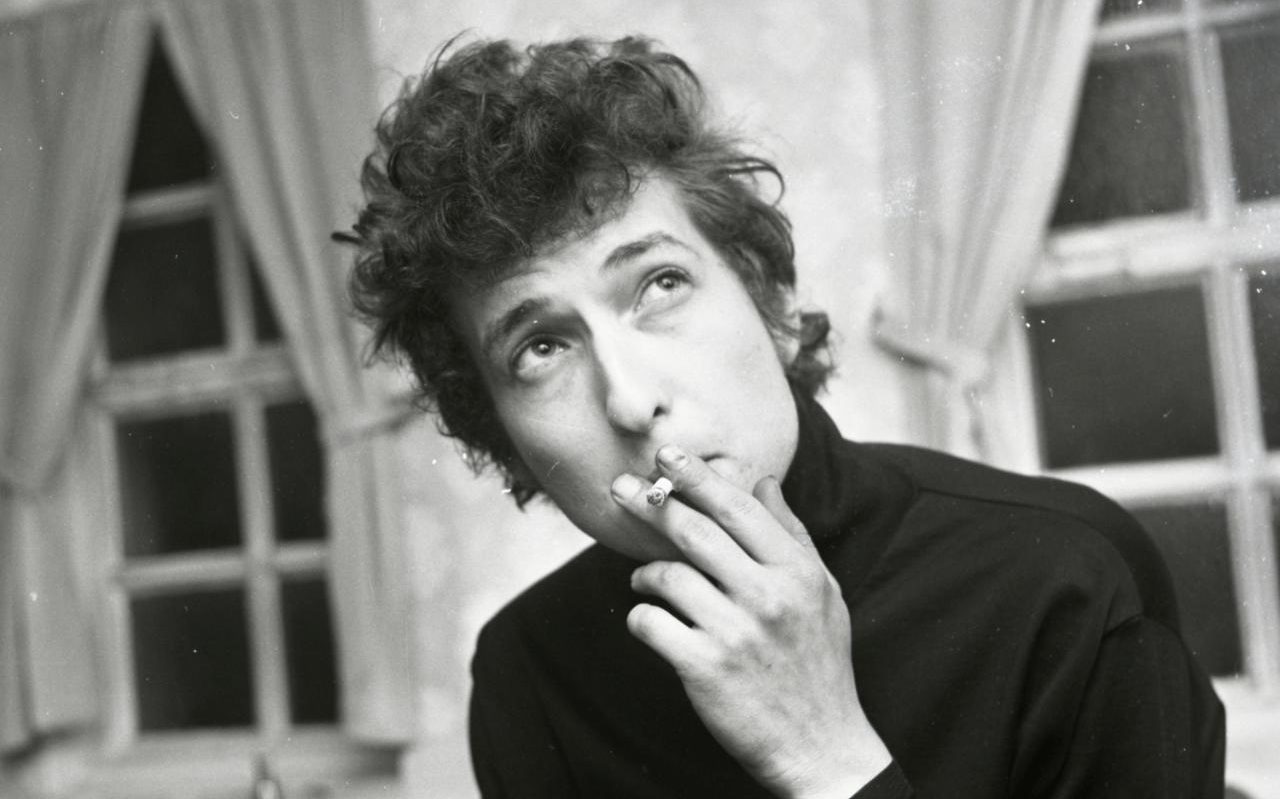

Bob Dylan was awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature last week for ‘having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition’. The news proved joyous for some – a travesty for others…

Can a song be literature? Why not? Because it isn’t bound in a book; didn’t wax lyrical; was not of lasting literary merit? Who decides something like that? What exactly is this thing called literature?

Whilst debate and discussion continues amongst scholars today about how we should define literature, it seems there are people out there who already have it pinned down, publishing their findings in comment sections of online articles. According to these ‘experts’, Dylan does not fall into the bracket of literature. You can’t help but notice the irony in this – the ‘Dylan’ from whom Robert Zimmerman gets his name is in fact the canonical poet, Dylan Thomas. Even the man’s name is rooted in literature.

Dylan has been hailed a modern bard; the word ‘bard’ seems particularly apt, for the origins of the English vernacular are steeped in the oral tradition. Consider Chaucer, it is clear from a glance that The Canterbury Tales was written to be spoken aloud. Literature, as we know it today, had its beginnings as a very vocal medium.

But there is bound to be an element of controversy with a Nobel Prize for something as subjective as literature. Dylan is not the first to be deemed unworthy of the award: in 2009, the Nobel committee was accused of being too Eurocentric when German novelist Herta Müller was awarded the prize despite many US academics having never heard of her.

The issue lies not with those who would have preferred Ngugi wa Thiong’o (Patrick French), or Morrissey (Jonathan Franzen), or any lesser-known or racially marginalised writer at all (Hari Kunzru). The issue is not with those who simply don’t like Dylan’s words, those who feel his lyrics are tethered too closely to pop culture: relevant perhaps then, but not now. These are opinions engaging with Dylan’s writing: indeed, one of the most exciting things about the announcement of any established literary prize is the aftermath, wherein academics rate or slate the winner with renewed ferocity, usually resulting in some fresh critical discussion about the work.

The issue lies instead with those who claim that Dylan’s work doesn’t qualify as literature.

Perhaps it is not conventional literature, yes: Dylan has never woven a plot as intricate as Tolstoy, sketched characters as caricatured as Dickens. If we disregard Dylan for the sake of argument, on the grounds that lyrics are not literature, what else is now not literature?

Lyric, as a genre, has its origins in Ancient Greece, wherein verse was accompanied with music. It seems these people who claim Dylan’s work to be ‘unliterary’ would not include the likes of Sappho – to whom Dylan is frequently compared – in their revised canon. Casting an eye to Ancient Rome, Catullus likewise would be disregarded in this literary purge: because his universally heart-rendering poems on his lover Lesbia just aren’t literature.

We can say goodbye to the Romantics, to Shelley, Byron, Burns, Coleridge – indeed, Professor Seamus Perry of Oxford University drew a parallel between the Romantics and Dylan, calling him ‘the Tennyson of our time’. But apparently Ozymandias or Kubla Khan are not literature, tarnished with this ugly lyric brush.

Arguably the most tragic losses of all are the swathes of Shakespeare. Think of the countless songs in various plays – The Tempest, Hamlet, As You Like It – all lost. Think of the sonnets that belong to this soiled genre of lyric, that are now no longer literature. Indeed, so much of Shakespeare is lyric, I doubt he would be eligible for the Nobel Literature Prize in this newly-narrowed world.

Besides, why should we define literature so narrowly? Literature’s definition is in a constant state of flux, with its limits continually challenged. We, as readers, perpetually decide and shape for ourselves what literature ought to be. Prose, poetry, drama, lyrics: if you liked the words, why not count it? I was ecstatic for Dylan, whose writing is more than deserving of this prize; but I was also delighted for literature as a whole, and its surpassing of yet more boundaries.

Serena Smith

image: telegraph.co.uk