A few months after its release, Jessie Jones reflects on the impact of Frank Ocean’s ‘Blonde’.

If you speak to any hip-hop fans about 2016, somebody, and something, will almost definitely be the first thing they mention: Frank Ocean and his stunning album ‘Blonde’. This was THE album. After 2012’s ‘Channel Orange’ the wait for Ocean’s follow up became the metaphorical internet version of a woman waiting for her husband to come back from war, staring out of the window and crying. Let’s face it, we were starting to get pretty infuriated and, personally, for my own sanity, I resigned early in the year to give up hope for the time being that it would, as promised, be this year. So when it dropped suddenly on 20th August, it was a relative surprise. We heard earlier in the year that the album had a name: ‘Boys Don’t Cry’. It was then announced it would be out in July. July came and went. Without much forewarning, it appeared, transformed into ‘Blonde’, accompanied in some record stores with a zine called ‘Boys Don’t Cry’.

This was the first suggestion that, not only was the album well worth the wait but it was going to be a real hip-hop milestone. With the visual album ‘Endless’, released the day before ‘Blonde’, and the existence of the accompanying zine, it finally seemed official: Frank Ocean is an artist. All musicians reside under this umbrella term as a loose and abstracted synonym for skill. But this is different. Not only had Ocean compiled a stunning album, but had made it intertextual and multi-media.

The visual album of course is not a new phenomenon spanning back as far as The The’s ‘Infected’, released in 1986. Other hip-hop artists have since followed such as Kanye West in 2010 and, earlier this year, Beyonce’s ‘Lemonade’. But this felt different. Frank felt different. The sound, texture, narrative and poetics of the album were completely different from anything that had ever existed in this sphere before.

Hip-hop changed the day this album was released.

Though that may seem a tad hyperbolic to some, hear me out: the rhetoric of hip-hop has never so openly and beautifully professed queerness, destabilised stereotypical masculinity and had such a sensitivity. All of that resonating through some of the most beautiful songs of the year.

Music made by black people, especially blues, has never shied away from the political. Nina Simone is perhaps the prime example of when a powerhouse musician harnessed their talents in order to enact civil rights change. In modern day America and Britain, with the increasing number of police brutalities and wrongful arrests, her music still resonates with profound importance. Artists like Kendrick Lamar could be called a direct inheritor of this tradition, harnessing the fictional narrative of Kunta Kinte of ‘Roots’ to remind the world of its still-rife imbalances.

Frank’s album however, is politically charged in another way. It’s Frank’s sexuality, rather than his racial identity, that takes centre stage on ‘Blonde’. In its very name the album sets up a narrative that challenges not only heteronormativity but gender binaries as well.

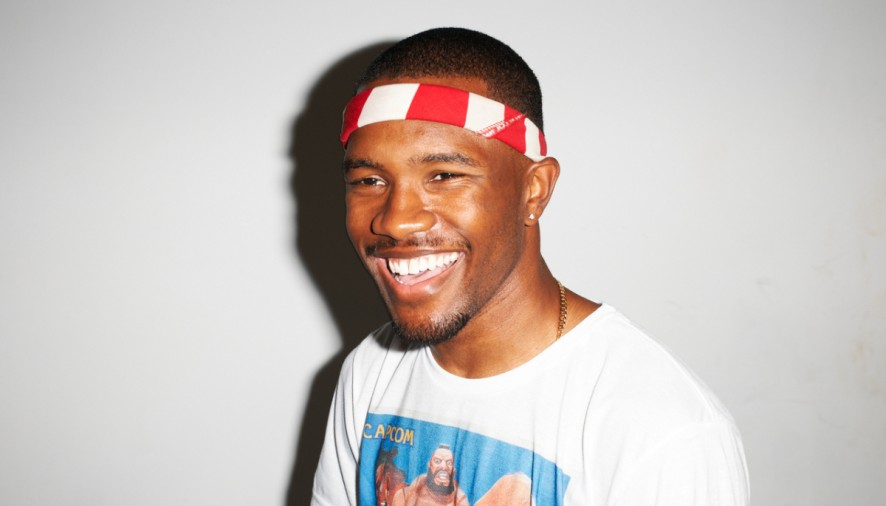

Frank has referred to the album both as ‘Blond’ and ‘Blonde’, the very title never settling on a gendered name, shifting from one to the other. The cover shows the artist, skin wet, without clothes, complete with green skinhead. His assumed nakedness is fitting for an album that is bare, raw, and unapologetically emotional. His green hair perhaps stands as a modern day equivalent of Bowie’s alien character Ziggy, a playful visual signifier of his identity on the fringes.

The power of the lyrics are not an explicit admission of sexual categorization. It’s the very rejection of these boundaries and limitations that make the album fluid and mysterious. It’s not deliberate that there’s a blending of nods to both the heterosexual and the homosexual, the lyrics containing ‘pussy’ ‘wet dreams’ and ‘gay bar’. This is not an album offered up as an explanation of queerness. This is not Frank explaining to the heteronormative world ‘what-it’s-like-being-a-queer-man’, readily set up, packaged and digestible. This is an album that one moves through and is meandered through, around and away from the usual heterosexual, hyper-sexualized narrative of hip hop.

Frank’s refusal to explain himself in explicit terms is why this album is so important. There is no allusion to Frank spearheading an LGBTQ+ rights campaign, but the subtlety with which gender and sexuality are questioned, is perhaps more of a gift to the queer community than a more explicit and angry proclamation would have been.

In ‘Self Control’ he sings ‘I came to visit, ‘cause you see me like a UFO’; perhaps another nod to the alien – there is just a vague and beautiful otherness to his identity.

In the same song’s chorus lies one of the clearest references to his position: ‘I’ll sleep between y’all’. Not only may he literally sleep between members of both genders, his socio-political position lies somewhere in-between two boxes to be ticked on an official form.

In ‘Seigfried’ the narrative of a traditional, middle class American dream is dissected and held up as a seductive but uncomfortable imposition. ‘Maybe I should move and settle, two kids and a swimming pool’ he sings before professing he isn’t brave. On the contrary Frank. The bravery of this album is explicit for all to see. With one of his last songs he describes his isolation outside a world that prescribes a ready-made ideal that doesn’t quite fit.

Not only is the album important, it’s an absolute dream to listen to. With a list of collaborators in the back of the zine, uncredited to specific songs, the list stands as a poster for the album’s excellence. It feels almost like a list of supporters, there to affirm the importance and artistry of the album. With a stripped down amount of instruments (compared to Channel Orange), there’s a spectral delicacy to the album, to go with Frank’s delicate, beautiful and intimate lyrics.

So if you haven’t already listened, make sure you remember the experience vividly. Because I have a feeling that will be one of those musical moments relayed for decades to come.

Jessie Florence Jones