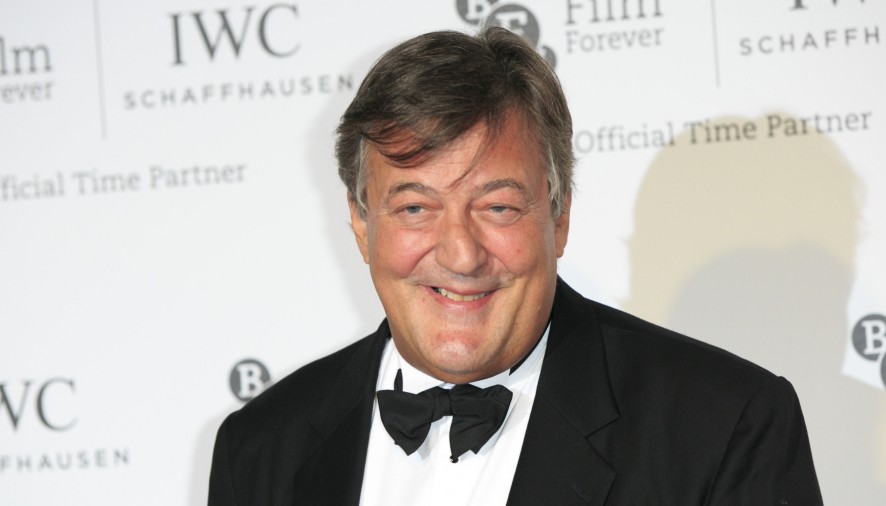

Stephen Fry, sometimes referred to as one of the UK’s ‘national treasures’, has always been one for speaking his mind, even if this entails offending people. As a champion of free speech, it is at the very least admirable that he is a man who puts this principle into practice. However, beyond his roles as an actor and public intellectual, he is also a key player in the campaign for raising awareness about mental illness, and happens to serve as the president of Mind, a charity focused on mental well-being. And as if this responsibility wasn’t enough, the well-known fact of his struggles with manic depression, commonly known as bipolar disorder, should have been more than enough to have made Fry think twice about his choice of lexis when approaching the issue of sexual abuse on a US talk show, The Rubin Report, perhaps doing so a little more tactfully.

Whilst much of the response on social media appears to have disregarded Fry’s comments within the context of a more extensive discussion on free speech, Fry’s claims that victims of sexual abuse should refrain from their ‘self-pity’ and ‘grow up’ didn’t do him any favours, instead conveying a lack of consideration towards the damaging impact such abuse can have on a person’s mental health, not least how lasting such damage can be.

Before reaching a verdict on where Fry has gone wrong, it is first necessary to look at the context of Fry’s overall discussion with US talk show host, Dave Rubin. Prior to the comments regarding sexual abuse being made, the two men were discussing free speech and censorship, with Fry adding that many plays contain unsavoury themes, including rape, and that these are ‘…terrible things and they have to be thought about, clearly, but if you say you can’t watch this play, you can’t watch Titus Andronicus, or you can’t read it in a Shakespeare class, or you can’t read Macbeth because it’s got children being killed in it…’ The overall point here is that it is against free speech to start banning works of art, particularly some of the greatest works of literature the English language has to offer, on the sole basis that it might upset some people. Whilst certain themes might resonate with people in a way that makes them uncomfortable, this does not warrant banning the works in question. And, if anything, such actions would shut down any hopes of having a dialogue about these issues, including that of sexual abuse.

Fry has since apologised for his comments on victims of sexual abuse, stating that, ‘I of course apologise unreservedly for hurting feelings the way I did.’ To claim that sexual abuse victims are ‘self-pitying’ is not going to help these victims. Healing from sexual abuse takes a long time and it is understandable that self-pity can, and has, become a problem for some of those affected. But scolding these people for their fragility in the face of this issue is not going to help them; supporting them and trying to understand them is the first step in helping them move on. Unfortunately, Fry didn’t make it apparent that he’d considered this when he made the remarks, but it would seem that ultimately he is aware of this. Meanwhile, however, the damage caused by such acts of abuse must not prevent us from exploring and discussing the issues at hand, even if some people can’t sit through a performance that tackles them head-on.

George Jackson

Image courtesy of Bafta/Whizz Kidd Entertainment/BBC