An artistic insight into racism, police brutality and mental health, ‘Oluwale Now’ is a daylong event celebrating the life and death of David Oluwale, a victim of terror at the hands of Leeds City Police. The Gryphon explores the life and death of David Oluwale.

His body found lying face down in the River Aire close to the sewage works. Old telephone directories used to fill his coffin. Buried in a mass paupers’ grave with nine others, the David Oluwale Memorial Association is committed to dignifying the life and death of David Oluwale. As a society, Britain believes itself to have come a long way in its treatment of ethnic minorities. However it is easy for Britain to celebrate its progressive future whilst forgetting its shameful past. The memory of David Oluwale’s life reminds the public that the treatment of ethnic minorities in the UK is not so black and white, and Leeds is shaping up to be the city at the centre of this campaign.

David Oluwale’s story is a harrowing account of utter disregard for human life that is ingrained into Leeds’s past and the history of the city’s police. The death of Oluwale in 1969 was the first known incident of a racially charged attack leading to the death of a black man at the hands of British police. This incident is also one of the only times an officer has received a sentence for being in some way related to the death of a suspect through police brutality. Nearly fifty years after his death, the University of Leeds will be partnering with the David Oluwale Memorial Association on 26th February 2016 to celebrate his life through music, art, and poetry. As much as this event is a celebration, it is also a reminder of the resonance Oluwale’s story has in today’s society, shining a light on police brutality and the failings of mental health services in reaching out to black, asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities.

Oluwale was a Nigerian migrant who came to Britain, aged just nineteen, in 1949, then a former British colony rife with poverty and unemployment. His aim? to secure a better future in the ‘Mother Country’. A stowaway on a ship carrying groundnuts, Oluwale arrived at Hull and was immediately arrested and sent to Leeds’s notorious Armley prison. Upon sentencing Oluwale, the magistrate at Hull police court declared that ‘[Oluwale] would have been better off staying at home digging groundnuts’, an unsettling outline of common, contemporary perspectives amongst the authorities towards migrants as a subhuman “other”.

Over 29 years in Britain, Oluwale became more familiar with the walls of Armley prison and what was then known as the Pauper Lunatic Asylum in Menston near Otley, being tossed between these and the streets of Leeds. Diagnosed as a schizophrenic, 10 of his 16 years between 1953 and 1969 were spent in Menston and it was here that Oluwale was subjected to various treatments that would eventually become detrimental to his mental health. ‘Liquid cosh’ largactil, a heavy tranquiliser, and electric shock therapy were used on Oluwale, often leaving him disorientated, twitching, and laughing for no apparent reason.

Yet it was more than the treatments he received in hospital that affected Oluwale’s state of mind. Two Leeds City Police officers, Inspector Geoffrey Ellerker and Sergeant Kenneth Kitching made it their mission to humiliate, belittle and subjugate Oluwale. Routinely beaten, battered, and verbally abused, what is striking is Oluwale’s determination to remain in the country. The only black, homeless person in Leeds at this time, Oluwale indented himself into the heart of Leeds City Centre, something that various artistic movements would echo years after his death. The mental and physical torture inflicted upon him, as well as the tiresome effects of being a black man in an unrelentingly racist Britain, fuelled Oluwale’s longing to return to Nigeria, seeking sanctuary from the Cruel Britannia that enticed and then rejected him.

On 18 April 1969, Oluwale was savagely beaten with truncheons by Ellerker and Kitching in a shop doorway near The Headrow for one final time. David Oluwale fled from his attackers, screaming and clutching the back of his head, to Leeds Bridge. Eyewitnesses on that night said that they saw two police officers chasing and then beating a ‘small, dark man’ unconscious, before kicking him into the river where he was found dead two weeks later. It was not until another officer in Leeds City Police brought into question the actions of Ellerker and Kitching that Oluwale’s body was exhumed and his death investigated two years later.

On 18 April 1969, Oluwale was savagely beaten with truncheons by Ellerker and Kitching in a shop doorway near The Headrow for one final time. David Oluwale fled from his attackers, screaming and clutching the back of his head, to Leeds Bridge. Eyewitnesses on that night said that they saw two police officers chasing and then beating a ‘small, dark man’ unconscious, before kicking him into the river where he was found dead two weeks later. It was not until another officer in Leeds City Police brought into question the actions of Ellerker and Kitching that Oluwale’s body was exhumed and his death investigated two years later.

In the Scotland Yard investigation, the trial judge described Oluwale as a ‘dirty, filthy vagrant’, with several trial witnesses affirming him to be a ‘dangerous man’. Kitching openly denied Oluwale’s humanity, declaring that he was ‘a wild animal, not a human being’, though these statements were not used in the trial. At the other end of the spectrum, to friends of Oluwale, he was gregarious and fun loving, known ‘Yankee’ due to his swagger and passion for westerns, until the humour and liveliness were knocked out of him by various figures of authority. As a black man, although only 5’5, Oluwale was painted as the violent attacker to be feared. Through the lens of black hyper-masculinity, Kitching and Ellerker defended their actions as protecting Leeds from the dangerous threat of the violent and savage black man, rhetoric we still see in today’s treatment of young, black men.

Ellerker and Kitching were jailed merely for a series of assaults against Oluwale and spent three years and twenty-seven months respectively in prison. The city then found itself in a debate of conscience; ignore this shameful mark on Leeds’s past or react to the abhorrent behaviour committed by authorities on the city’s streets. Deep embarrassment and shame towards the police struck the population of Leeds and swiftly the treatment of Oluwale in their home environment made distant, contemporary stories of violence and oppression more pertinent. At Leeds United’s football ground, Elland Road, Oluwale’s flame burned bright, with players and spectators chanting ‘The River Aire is chilly and deep, Ol-u-wale. Never trust the Leeds police. Ol-u-wale’.

John McLeod, professor of Postcolonial and Diaspora literatures in the School of English at Leeds, will be hosting a conversation with Guardian journalist Gary Younge at ‘Oluwale Now’. McLeod outlined that, ‘if we want to change the world you have to think and write about the world differently, and literature is where we go to think and write about life differently’. This is exactly where the people of Leeds went to celebrate Oluwale, refusing to let him be forgotten.

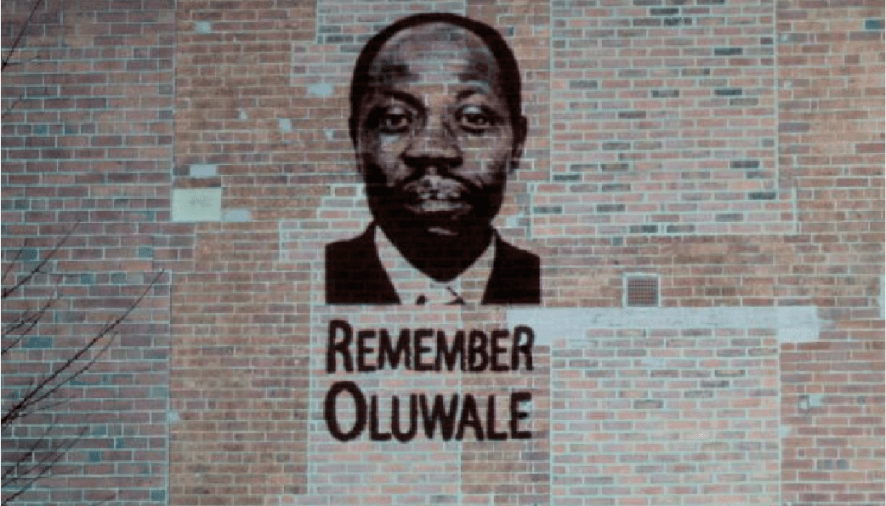

Struck by disappointment and guilt, art became the facilitator for the city’s reaction. Oluwale’s story caused a national scandal, prompted by a radio play written by Jeremy Sandford called Smiling David, though this story of terror and abuse had almost been forgotten about until police paperwork on the case was declassified under the 30-year rule. This moment inspired Kester Aspden’s book Nationality: Wog, The Hounding of David Oluwale, published in 2007. Aspden took inspiration for the book title from Oluwale’s suspect form, where his nationality was denoted as ‘wog’. Literature and art allow Oluwale to be the protagonist in Leeds’s historical narrative, refusing to let him be lost into the city’s murky past. Prolific writers such as Caryl Phillips in his 2007 book Foreigners and Linton Kwesi Johnson’s poems Night of the Head and Time Come, as well as many other poets and filmmakers, have put Oluwale at the centre of their art as a figure resistant to oppression. These are all works that commemorate Oluwale’s struggle whilst reasserting Leeds as a polycultural city built on migration and made greater by its diversity, defying Kitching and Ellerker’s vision of an oppressive, white-washed city.

The David Oluwale Memorial Association strives to keep Oluwale’s story at the heart of discourse on police brutality and mental health in the BAME community, using Oluwale as a reminder of the effects of institutional and diurnal racism. Dr Andrew Warnes, reader of American Studies in the School of English and one of the organisers of Friday’s event with Max Farrar, says that he wants this day to articulate and showcase the ‘eloquence of the cultural response’ to Oluwale’s death. Dr Warnes affirms that ‘[Oluwale Now] is not just about Leeds, but the way in which stereotypes circulate within police forces and culture in general and the extreme overreactions against individual vulnerable black men and women’. Welcoming journalist Gary Younge to talk of his experience of the Black Lives Matter campaign in the USA, Warnes hopes the event will underline the resonance of Oluwale’s story and its ‘horrible echoes’ in the treatment of young, black men in America today, in ‘an attempt to try and ask why this is happening’.

Nearly fifty years after his death, though it cannot be said that nothing has changed for the treatment of ethnic minorities in Britain, the memory of David Oluwale calls into question the resonance of similar issues affecting the BAME community in Britain and worldwide today. In the UK, black people are still overrepresented in prisons and, although not on as wide a scale as America, it is not unheard of for a black man to be shot dead by police in the street. High-profile cases of the shootings of young black men such as Stephen Lawrence and Mark Duggan by police force us to question to what extent ethnic minorities are valued and respected members of society. These concerns are echoed by the treatment of migrants and the increase in race-related crimes, largely targeted at the Muslim community. The suicides of Sarah Reed and Faiza Ahmed, two young black women with mental health problems, further indicate the failings of the state. Black Britons today are struggling to have faith in their country when it betrays them by accommodating institutional racism and a facilitating a seemingly never-ending war on black bodies.

If Oluwale’s tragedy should bring a single message of positivity, it is one of resistance and empowerment. Despite being viewed as ‘human rubbish’, black, and homeless, Oluwale upheld himself as a citizen, reclaiming Leeds as his city as much as it was Kitching and Ellerker’s. Oluwale is a signifier of all that we must embody to fight against figures of violence and oppression worldwide. Professor McLeod argues that though ‘it is tempting to build a legacy around [Oluwale’s] death’, it is the fact that, according to Dr Warnes, Oluwale ‘acted in the way he had every right to act, as a member of this community’ that should remain prominent. McLeod and Warnes echo each other’s statements, agreeing that Oluwale was ‘a representative of changes, pointing towards the Leeds of now’ and ‘reminding us of what we are’.

Though Oluwale’s memory lingers in the shadow of Leeds’s past, many are acting to place it at the city’s heart. The David Oluwale Memorial Association are currently planning to build a memorial garden in Leeds City Centre, a type of ‘horti-counter-culture’, directly confronting diurnal and institutional racism, and asserting Oluwale’s presence, just as he did, at the centre of a civic public space. Appropriately, ‘Oluwale Now’ takes place during Black Future’s Month, ‘a deliberate reinterpretation of the resistance and resilience of Black people as illustrated through art’. The David Oluwale Association and numerous poets, writers, and artists will continue to use the remarkable past of Oluwale and many others like him to shape black futures: celebrating, liberating, and empowering the oppressed and forgotten.

Jodie Yates

‘Oluwale Now’ takes place today (Friday 26th February) with events running in various locations from 14.30-19.30. More information can be found here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/oluwale-now-tickets-20892190103

Images: The David Oluwale Memorial Association, Nao Takahashi