Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, wrote a letter to Apple customers last week. Posted on the company’s website, the tech boss explained that the company would not honour a request made by the FBI to provide a ‘backdoor’ to encrypted iPhones. This decision to avoid developing a tool for the US intelligence agency, which would enable them access to encrypted data, was predicated on the belief that such actions would ‘undermine the very freedoms and liberty [the US] government is meant to protect.’ Cook has made something of a bold move in what can easily be perceived – at least on the surface – as an act of corporate defiance against the state, and for the benefit of Apple customers. In an age where data is easily gathered and accessed, the issue of who can view a person’s data and how such data is used has become a serious one, particularly in light of exposés from the likes of WikiLeaks and Edward Snowden in recent years.

The FBI request was made in conjunction with the investigation of a terrorist attack in San Bernardino California last December, a massacre that led to the deaths of fourteen civilians. It is clear that the agency want access to the mobile device of one of the perpetrators, in the hope of obtaining encrypted data that could be of use to them in the investigation, if not helping to prevent further attacks. The point however, is that Apple have already done everything within the confines of legality to help the agency. Although judges have ordered Apple to follow through with this new proposal the potential consequences of creating such a device render it, in Cook’s words, ‘too dangerous to create’.

It is evident that creating this device would likely put the data of many Apple customers under scrutiny. Such a device could fall into the wrong hands and be used for purposes less noble than the investigation of terrorists – this concern serves as the main reasoning behind Cook’s stand. Apple is already in a legally binding position to hand over information to the state that could be perceived as a threat to national security, if not helpful in preserving it. In his letter, Cook makes it clear that the company has always complied with ‘valid subpoenas and search warrants’ issued by the FBI. An admission of this kind is hardly a surprise, given the fragility of data security in the face of retaining national security. Only the Apple executive’s concern, in this instance, is that the device would enable people to hack into any iPhone without having to beat the mechanism that encrypts the phone’s data. At present, if the right settings are applied, an iPhone’s data can be scrubbed immediately if an unwelcome user fails to enter the right passcode within 10 attempts. This setting provides numerous benefits to iPhone users, from the protection of contacts, photos and social media accounts, all the way to safeguarding more critical information, such as banking and health details. The creation of a device that breaks through this mechanism with next to no effort would mean that in cases of theft or hacking, criminals who’ve obtained the device (and they will find a way, if such a device is created) would have an easy way into the mobile data and subsequent personal details of any iPhone user they prey upon. Note also that over 700 million iPhones have been sold worldwide since the iPhone was first launched in 2007. That figure translates into a plethora of users, even considering the iPhones that will have been broken and disposed of in that time.

We live in an age of people leading increasingly public lives, particularly in the online world. With more and more people being able to learn almost anything about who we are, which apps and websites we use, where we like to go out and who our friends are, and all this with the mere swipe or click of a button, there is a genuine need for some degree of privacy and to ensure that this privacy is protected. Personal privacy is not only beneficial to our sense of dignity, but more so to our mental health. It is also, in some cases, necessary for our personal safety. If we were to live in a world where people are unable to keep anything to themselves, then they are exposed and unable to differentiate between the private and public spheres of everyday life. The little privacy that remains for people today is already being eroded, thanks to data storage and social media. To create a device that enables encrypted data to be accessed with next to no effort is a further erosion of this privacy. As a company, Apple has an obligation to protect the privacy of its customers, be they in the USA or elsewhere. And it must be stressed that this is not just a problem for the USA. Apple has an estimated number of customers that stretches beyond 500 million people globally. Many of these will be iPhone users, all of whom will expect their privacy to be protected, regardless of where they’re living in the world.

It can’t be denied that government is playing an increasingly active role in the management of various aspects of our lives. Our data is no exception. Whilst it is understandable that governments want to gain as much information as possible in order to prevent further terrorist attacks like San Bernardino, the risks of creating the device requested, and putting civilians around the world and their privacy in danger, are too great for the sake of hacking into one wrongdoer’s phone. What’s more, once the device is obtained and replicated by international criminals, be they terrorists or otherwise, the blame will be projected onto Apple. Cook is being prudent in trying to block the creation of such a device under his watch. Most executives who want to stay on the good side of their customers, from both a human and business perspective, would do the same.

George Jackson

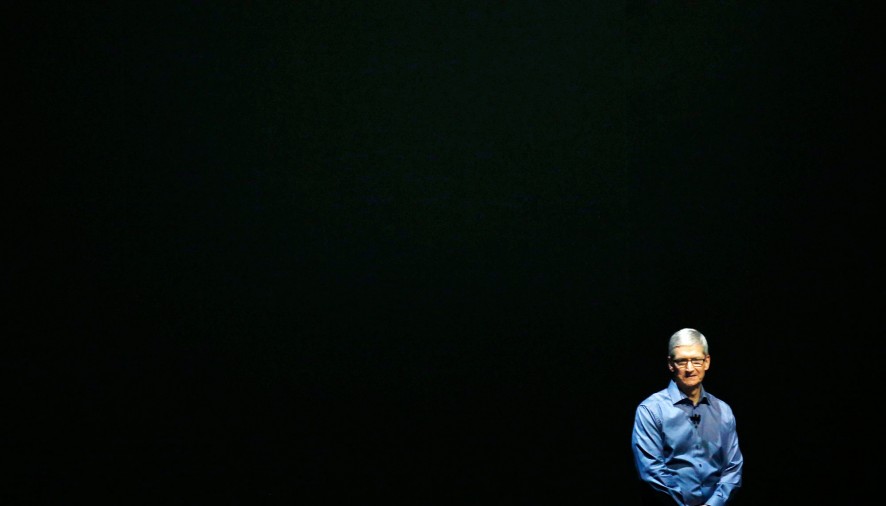

Image courtesy of Beck Diefenbach/Reuters