‘Politically correct’ has become a loaded term – often people are publicly slandered as being racist or bigots, for expressing their thoughts. So where does the distinction between sensitivity and compassion, and outright slander lie? The Gryphon explores Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka’s, views on the subject – and what this means for the discourse of Black History.

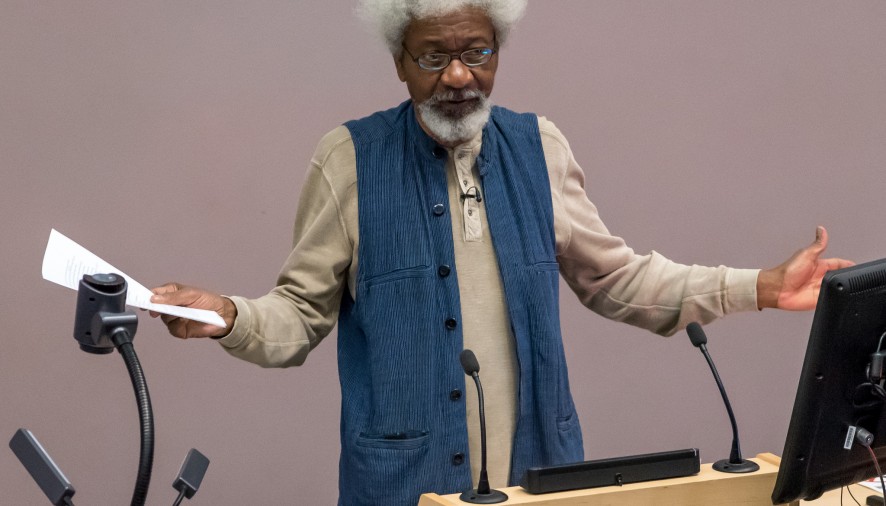

Attending Wole Soyinka’s lecture ‘Narcissus and other Pall Bearers: Morbidity as Ideology’ last Thursday, I was somewhat surprised at his apparent discontent with political correctness. As someone who spent twenty-two months imprisoned during the Nigerian civil war, for which a massive factor was ethnic division between the country and the subsequent effects on governance, you could perhaps assume him to be an advocate of such self-declared ‘correct’ ways of thinking. However, his time imprisoned seems to have had the opposite effect: far from allowing himself to be consumed by negativity, he has been empowered by his unjust time in prison to identify what political correctness really is.

In his lecture, the Nobel Laureate stated that he feels that political correctness should be “abandoned”, as only then can we confront dictators and Narcissists, or as he termed it “the phenomenon of power”, in a manner that is free of political connotations or assumptions of a lack of understanding of another culture. At its core, his argument challenges political correctness as an assumption of all cultural identities as untouchable. Rather than being respectful of Black Minority Ethnic groups, this is actually damaging for them: allowing people to continue to dictate societies, whilst hiding behind culture or tradition.

In the 2010 UNESCO conference, he indicated that he felt that it is a concept that actually works against cultural openness – hindering the very cause it was designed to help. In this speech, Soyinka defined the act of political correctness as “an assumption of standing on high moral ground and presuming that others cannot quite attain that moral height”. Such condescension may never lead to empowerment: civil rights movements have always defined themselves on a base of solidarity and strength. By treating African diaspora as though they need to be protected from certain ideas, we establish a distinction between ‘them’ and ‘us’, in which we patronise the ‘them’ by labelling them as a vulnerable group, further maintaining the idea of the ‘us’ as superior. So where can this ‘language’ fit into an ever-growing discourse of Black History?

For many years, white supremacy has distorted and hidden histories that did not meet the charade of perfection – what Soyinka terms “invisible cultures”. We pretended they did not exist. But in a more liberal  time, when we have come to reinvestigate and retell these stories, many people still continue to shy away from the task – perhaps, for fear of being politically incorrect or contributing in the wrong way. Anxiety of further appropriating a history and culture that we have already taken so much from comes about, so it is simply ignored instead. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, slave narratives are becoming more and more recognised: from Frederick Douglass’s memoir, to Toni Morrison’s contemporary fiction, to the widely-renowned film adaptation of 12 Years a Slave. But how often do you read a narrative from the slave driver’s perspective, accepting our role in this unspoken history? A phenomenon that we caused, white people should definitely be engaging with and partaking in black histories: reinvestigating the very cultures their predecessors rendered invisible.

time, when we have come to reinvestigate and retell these stories, many people still continue to shy away from the task – perhaps, for fear of being politically incorrect or contributing in the wrong way. Anxiety of further appropriating a history and culture that we have already taken so much from comes about, so it is simply ignored instead. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, slave narratives are becoming more and more recognised: from Frederick Douglass’s memoir, to Toni Morrison’s contemporary fiction, to the widely-renowned film adaptation of 12 Years a Slave. But how often do you read a narrative from the slave driver’s perspective, accepting our role in this unspoken history? A phenomenon that we caused, white people should definitely be engaging with and partaking in black histories: reinvestigating the very cultures their predecessors rendered invisible.

It is a tricky topic to discuss, again for fear of being politically incorrect, but in constantly self-censoring ourselves in any discussion pertaining to race, we are constantly oppressing potential healthy debate. In light of this, how are we ever going to form a coherent discussion and conquer the very barriers we want to overcome? J W Basher acutely summarises this concept in his book, Intimidation by Political Correctness:

Political correctness is counterproductive to good change, for it stifles debate… If one cannot talk about something, he cannot debate it. If he cannot debate it, he cannot isolate the issue or problem. If he cannot isolate the issue, he cannot correct it.

And it can be counterproductive in other ways too. In 2006, white Tory MP Bernard Jenkin came under fire for using the term “coloured people” in a radio interview – though he perhaps thought he was being sensitive, Toyin Agbetu, a social rights activist and founder of “The Stuff You Should Know” initiative, explains that this one-size-fits-all term actually strips people of their identities and reduces them to a “superficial physical identifier” as opposed to a person with a history and an ethnic background.

Nonetheless, sensitivity is always required when discussing other people’s cultures, backgrounds, and identities. Whilst it would be nice to assume that everyone in this day and age is compassionate enough to recognise social cues, we still cannot say that we live in a world in which every person considers all cultures as equal. As such, political correctness is not completely defunct – it must still be used as a guideline of what we should and should not be doing. But we should not bind ourselves with constrictions either – how can rhetoric on Black History ever be established if people are just not talking? Perhaps a new discourse needs to be established – one of both honesty and compassion, as opposed to just one or the other.

Molly Walker-Sharp

Images: Jodie Collins